From Glorification to Humiliation: Reassessing Philippians 2:6-8 (Part 1)

From Glorification to Humiliation: Reassessing Philippians 2:6-8 (Part 1)

Philippians 2:6-8 is a testament to the incredible humility of Jesus. Paul vividly describes it as the voluntary transition from the “form of God” to the “form of a servant.” But what exactly do these phrases mean? And when during his life was Jesus in such contrasting states? These questions can be answered in a few different ways. The interpretive route one takes, however, depends upon the assumptions one brings to the text.

In this series we will examine several common assumptions that underpin the popular “incarnational” interpretation. We will also consider the exegetical reasons why Paul’s famous Carmen Christi is best understood not as Jesus transitioning from a pre-existent state to a human state but rather from a glorified state to an afflicted state.1

Structural Considerations

Philippians 2:5-8 (RSV) — 5 Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, 6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, 7 but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. 8 And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross.

The interpretive route taken by most theologians is marked by one key assumption: since the statement “being in the form of God” occurs before the statement “being born in the likeness of men,”2 Paul must be claiming that Jesus existed before he was born. This conclusion is encouraged by the punctuation in verse 7. Most English translations put a comma after “servant” and a period or semicolon after “men,” supporting the inference that Jesus “emptied himself” and “took the form of a servant” by being “born in the likeness of men.”3

But in fact the oldest copies of the Greek New Testament contain no punctuation. This is seen in the New Testament Papyri p46, which contains our text from Philippians 2.4 Moreover, the punctuation marks found in our English translations are editorial decisions made by the translators. While they are generally helpful, they aren’t guaranteed to accurately reflect the original flow of thought in every case. Sometimes they can even unintentionally obscure the author’s intent.

In the case of Philippians 2:6-8, we are dealing with a formal hymn, and the structure of this hymn has been debated by scholars. Trinitarian scholar Moises Silva highlights one proposed structure that results in punctuation very different from what we find in most Bibles. He notes that a “striking parallelism appears when verses 6-8 are arranged as two stanzas of four lines each.”5 A literal translation of the passage arranged in this way reads as follows:

Who, being in the form of God,

Who, being in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God a thing to be seized

but emptied himself,

having taken the form of a servant.

Having become in the likeness of men

and having been found in visible condition as a man,

he humbled himself,

having become obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

Silva notes several solid linguistic reasons for such an arrangement, including the fact that “the first stanza begins and ends with the noun morphe (form), whereas the second stanza begins and ends with the participle genomenos (having become).”6 Furthermore, he adds that “each line of the first stanza finds some parallelism in the corresponding line of the second stanza.”7

This compelling alternative arrangement shows that the structure presented in most Bibles is not as reliable as one might think. Our interpretive starting point should therefore be the Biblical background for pivotal phrases such as form of God, equality with God, emptied himself, and form of a servant. We must also consider the contrasts and parallelisms Paul might be making with these phrases, in light of his teaching elsewhere in scripture.

Following Silva’s structure, we will consider each key phrase in detail below. This post will evaluate the first stanza line by line, and the next post will tackle the second stanza.

Stanza 1

Who, being in the form of God,

The phrase “form of God” (morphe theos) is the first major challenge confronting the interpreter. It occurs nowhere else in the Bible and scholars have therefore debated its exact meaning. But it is also the most important one to get right, because it drives our interpretation of the rest of the hymn. The predominant view is that “form of God” describes Jesus in a divine and pre-existent state. But does the linguistic and contextual evidence support this?

Thayer’s Greek lexicon defines morphe as “the form by which a person or thing strikes the vision; the external appearance.”8 The NIV translators boldly render it “nature” in Phil. 2:6, but they do this by rejecting its scriptural usage in favor of the way it is used in Greek philosophy. Peter O’Brien observes that “there is very little evidence to support the view that Paul uses morphe in such a philosophical sense.”9 Thus most Bible translations wisely stick to the word “form.”

When used of living beings in the Greek OT (LXX), the word morphe virtually always refers to embodied humans.10 In the NT, this noun only appears three times and always refers to Jesus (Phil. 2:6, Phil. 2:7, Mk. 16:12). Outside of the phrase we are presently evaluating, it always refers to Jesus in a physical body.11 This data, taken together with Paul’s explicit teaching that God is by contrast invisible,12 gives us good reason to think that “form of God” (morphe theos) refers to Jesus in a physical body, visibly representing the invisible God.

But what exactly does it look like to be “in the form of God,” and when did Jesus embody this particular form? These questions invite us to dig a little deeper into the background of the phrase. The closest we come to “form of God” (morphe theos) in the rest of Paul’s epistles is the phrase “image of God” (eikon theos). And it turns out that the concept of Christ as God’s “image” is developed using verbs derived from the noun morphe. Let us consider the evidence, beginning with a key passage found in 2 Cor. 3:18:

2 Corinthians 3:18 (ESV) — And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed [metamorphoumetha] into the same image [eikon] from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit.

The verb metamorphoumetha is derived from the noun morphe. It means to change into another form, and that form is specified here as the eikon of Christ. Thus Paul essentially says that “our form is being changed into the same glorified image of Christ.” This tells us that he regards form and image as synonyms.13

The parallel use of image and form here is noteworthy because it specifically refers to the glorious image/form of Christ, who in turn is described as the glorious “image of God” in the next chapter:

2 Corinthians 4:4 (ESV) — In their case the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelievers, to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God [eikon theos].

By extension, therefore, “image of God” (eikon theos) and “form of God” (morphe theos) are most likely equivalent terms. Paul’s point in 2 Cor. 3:18 is that we are gradually being changed into the form of the Second Adam, who is himself presently in the form of God. This transformation has both an inward and outward element. The inward spiritual element begins in the present age and is consummated by the outward physical element at the resurrection.14 The final outward aspect of our transformation is emphasized in Rom. 8:29:

Romans 8:29 (ESV) — For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed [summomorphon] to the image [eikon] of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. 30 And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified.

Thayer defines the word summomorphon as “having the same form as another.” In this context it means that our bodies will be changed into the form or image of Christ’s present glorious body at the resurrection. Significantly, the same word is used to describe the same concept in Phil. 3:21:

Phil. 3:20-21 (NASB20) — 20 But our citizenship is in heaven, from which we also eagerly await for a savior, the Lord Jesus Christ, 21 who will transform the body of our lowly condition into conformity [summomorphon] with His glorious body, by the exertion of the power that He has even to subject all things to Himself.

Scholars have noted that “conformed (summomorphon) to his glorious body” in Phil. 3:21 appears to recall the phrase “form (morphe) of God” in Phil. 2:6.15 Indeed, the Cornerstone Biblical Commentary documents six lexical similarities between Phil. 3:20-21 and Phil. 2:6-11, indicating a close relationship between the passages:

- in the form (morphe) of God, 2:6a / conformed (summorphon) to his body of glory, 3:21

- being (huparchon) in the form of God, 2:6a / citizenship exists (huparchei), 3:20

- likeness (schema) as a human being, 2:7b / change likeness (metaschematisei), 3:21

- he humbled (etapeinosen), 2:8 / humble condition (tapeinoseos), 3:21

- Lord Jesus Christ (kurios Iesous Christos), 2:11 / Lord Jesus Christ (kurion Iesoun Christon), 3:20

- glory (doxan), 2:11 / his body of glory (doxqs), 3:21

Given the background we’ve already examined in Paul’s other letters, this six-way parallel makes it very probable that Jesus “in the form of God” (2:6) refers to “his body of glory” (3:21). It is therefore unsurprising that Paul chose the present tense for the participle clause “being in the form of God.”16 There are five total participle clauses in the Carmen Christi, and of these, only the first is in the present tense. And only the first clause also described the present state of Jesus at the time Paul wrote to the Philippians, as shown in the table below:

| Participle Clause | Verb Tense | True at the Time Paul Wrote the Letter? |

| Being in the form of God (2:6) | Present | Yes (his current state of being) |

| Having taken the form of a servant (2:7) | Aorist | No (action occurred prior to his death) |

| Having become in the likeness of men (2:7) | Aorist | No (action occurred prior to his death) |

| Having been found in external condition as a man (2:8) | Aorist | No (action occurred prior to his death) |

| Having become obedient unto the point of death (2:8) | Aorist | No (action occurred prior to his death) |

The linguistic evidence we’ve discovered so far gives us a much better picture of what it means for Jesus to be “in the form of God.” We know it most likely refers to Jesus as an embodied human being. We also know that in Paul’s writings, “the form of God” is very closely related to the “the image of God,” which is always used to describe Jesus in a glorified state. And we know that the participle clause “being in the form of God” is in the present tense – unlike the four remaining participle clauses – which implicitly connects it with Jesus’ present glorious body.

It seems evident, then, that Paul has placed the starting point of the hymn at a point in Jesus’ mortal life when he had the same form that he is presently in. There is in fact just one event that fits this bill:17

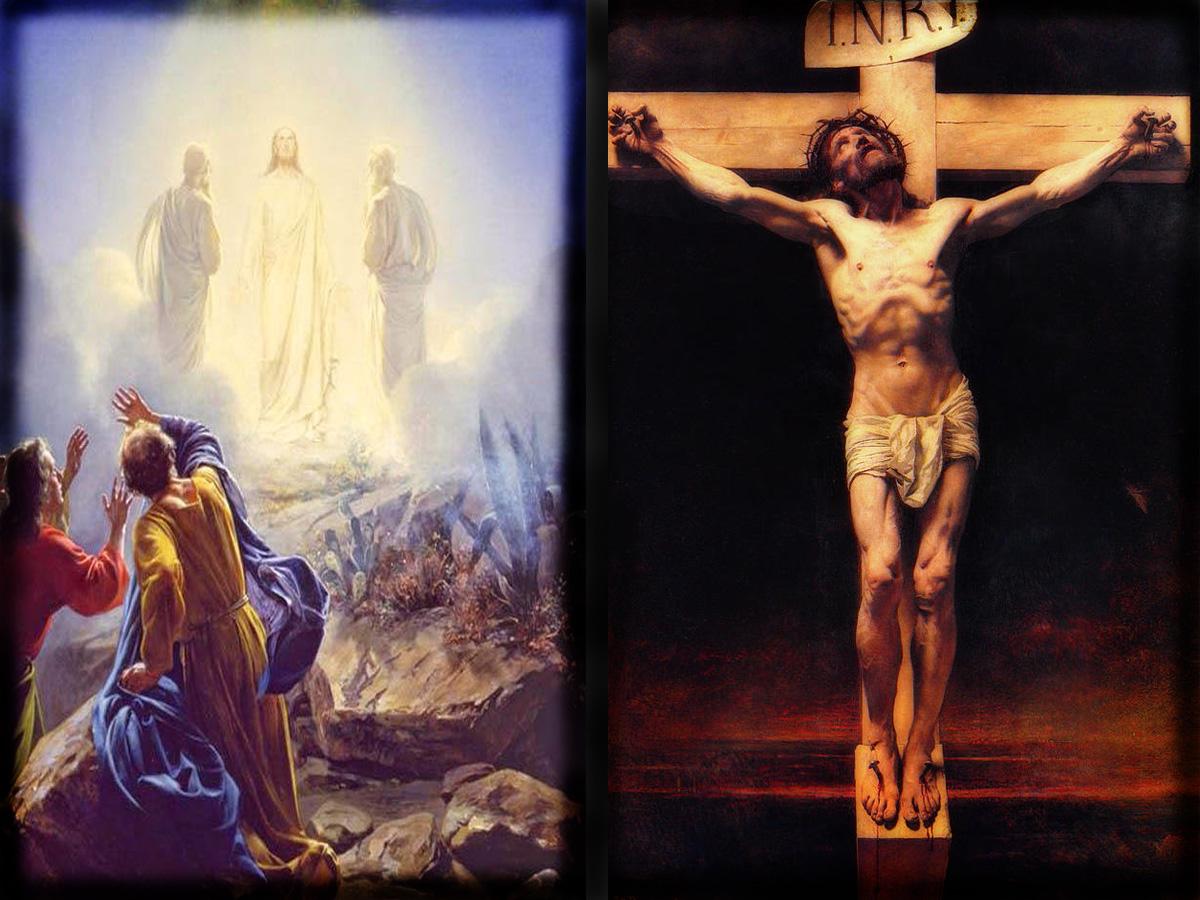

Matthew 17:2 (ESV) — And he was transfigured [metamorphothe] before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became white as light.

Thayer defines metamorphothe as “to change into another form.” Jesus outwardly changed into a form that was different from his normal form – and the difference is that his body was visibly glorified. One significant reason Paul’s hymn would focus on this event is that the transfigured form of Jesus recapitulates the original form of Adam.

Just as Adam was “crowned with glory and honor” (Ps. 8:5) before the fall, so too at the transfiguration Jesus received “glory and honor” (2 Pe. 1:17). But like the pre-fall Adam, Jesus’ glory and honor was not yet permanent. To embody it eternally, he too had to obey God’s will regarding a tree.

There is even a fascinating parallel between Jesus in his transfigured form and the Jewish tradition that Adam was in such a form prior to the fall:

Adam’s heel outshone the globe of the sun; how much more the brightness of his face! (Middrash Rabbah)

We may further observe that before, during, and after Jesus was in this transfigured state of the pre-fall Adam, he specifically drew attention to his impending death and subsequent resurrection.18 This indicates that his altered form was also his predestined resurrected form — a glorious body that is indeed, by all indications, the visible “form of God.” Paul saw this form on the road to Damascus, while Peter, James, and John saw it just prior to the crucifixion.

Therefore the transfiguration is a strong candidate for the background Paul had in mind in Phil. 2:6a.19 As we examine the remainder of the Philippians hymn, we will consider how the “form of God” as a reference to the transfiguration makes the best sense of the Carmen Christi.

did not regard equality with God a thing to be seized

The phrase “equality with God” (isa theo) is another expression assumed to reveal that Jesus is inherently divine. It is taken as a statement of identity, so that “equality with” is mentally replaced with the word “being.” But the Biblical usage of this phrase tells a very different story. It appears one other time in the New Testament, where it is also applied to Jesus:

John 5:18 (ESV) — This was why the Jews were seeking all the more to kill him, because not only was he breaking the Sabbath, but he was even calling God his own Father, making himself equal with God [ison theon].

Here the word “equal” (isos) compares two individuals who are father and son. A son is self-evidently not the same being as his father, and thus being “equal with” God is not a statement of identity but of similarity. We find another example in Lk. 20:36, where people are said to be “equal with” angels (isangelos). This doesn’t mean people are angels, but rather they are like angels in a particular way.

In ancient near eastern culture, to say a son was “equal with” his father was to say he had been given the same authority as his father. He served as his father’s agent, possessing the authority to conduct his father’s affairs on his behalf. Craig Keener writes:

[W]hen one sent one’s son (Mark12:6), the messenger position was necessarily one of subordination to the sender. Although the concept of agency implies subordination, it also stresses Jesus’ functional equality with the Father in terms of humanity’s required response: he must be honored and believed in the same way as must be the Father whose representative he is (e.g., John 5:23; 6:29)20

Jesus’ antagonists in this scene knew the Messiah would be the supreme Davidic Son of God (2 Sam. 7:14). They also knew the Messiah would be functionally equal with God, possessing the royal authority to act on God’s behalf (Ps. 2:7-12, Dan. 7:14). But they emphatically denied Jesus was the one God had chosen for this role (Jn. 9:29).

In other words, Jesus’s enemies did not accuse him of falsely claiming to be God himself, but rather, they accused him of falsely claiming to be God’s Messiah. Jesus’s reply confirms this. Stefanos Mihalios points out that “[the] purpose of Jesus’s response, starting from [John] 5:19, is to clarify his relationship to the Father…to conclude that he is the unique Son of God, Israel’s representative king, and the coming Messiah.”21

With this background in view, Phil. 2:6 tells us that while Jesus was “in the form of God,” he did not regard his royal messianic authority something to be seized.22 Since “form of God” most likely describes Jesus in a physically glorified state, Paul appears to be drawing a contrast between Jesus’ visibly authoritative appearance and his humble frame of mind. This again points us in the direction of the transfiguration.

Just before that spectacular event, Jesus began to warn his disciples that he would soon suffer at the hand of his enemies. When Peter objected, Jesus rebuked him by saying that “you are not setting your mind (phroneis) on the things of God” (Matt. 16:21-23). This statement implies that Jesus, by contrast, was setting his mind on the things of God — which entailed suffering on behalf of others. It is precisely this “mind” (phroneistho) of Christ that Paul encourages his readers to imitate in Phil. 2:3-5.

During the transfiguration itself, God announced Jesus’ equality with him, declaring: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him” (Matt. 17:7). Indeed, Jesus’ shining face and gleaming white clothing visibly signified his moral purity and his exalted destiny. Peter was so taken by this royal show of glory that he inadvertently tempted Jesus to usher in the kingdom right then, suggesting they set up three tabernacles on the mountain.

Peter’s comment may well have been a reference to the Feast of Tabernacles that is to be celebrated on Mt. Zion when the Messiah reigns (Zech 14:16). Darrell Bock has pointed out that the voice of God may have interrupted Peter in part as a rebuke “for suggesting that now is the time to celebrate the entry of the eschaton.”23 Yet Jesus refused to avoid the cross by seizing his Messianic kingship in that glorious moment.

His attitude while visibly manifesting “the form of God” was the epitome of humility: he spent the entire time discussing with Elijah and Moses his intention to sacrifice himself for the sake of his beloved people, who could not save themselves (Lk. 9:30-31). Thus, while the first Adam in all of his glory decided to disobey his Father’s will regarding a tree, the second Adam in all of his glory purposed to obey his Father’s will regarding a tree.

but emptied himself,

Scholars have long debated what it meant for Jesus to “empty” (ekenosen) himself. However, Gordon Fee points out that this debate “has been generated by scholarship, not by Paul or Pauline ambiguities.”24 The verb ekenosen has a well-established meaning that Paul used elsewhere in his writings. It means to “make void,” and it is used here in a metaphorical sense that is equivalent to the idea of pouring something out.25

Silva correctly states that it “encapsulate[s] for the readers the whole descent of Christ from highest glory to lowest depths.”26 He assumes, of course, that being in “the form of God” refers to a pre-existent divine state and therefore thinks Christ’s voluntary emptying began with his birth. But this conflicts with the way scripture consistently describes the Messiah pouring himself out.

Isaiah 53:12 proleptically declares that he “poured out his soul to death and was numbered with the transgressors.” Jesus used the same imagery at the Last Supper. Taking the cup of wine, he told the disciples: “This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood” (Lk. 22:20). And Paul likewise uses the imagery of “pouring out” as a metaphor for sacrificial death:

Philippians 2:17 (ESV) — Even if I am to be poured out as a drink offering upon the sacrificial offering of your faith, I am glad and rejoice with you all”

Thus the “emptying” of the Messiah most likely has in view the specific events surrounding his suffering and death. At the transfiguration, when Jesus was in the most glorious form of his mortal life, he was laser-focused on his decision to “pour out” that life (Lk. 9:31-32). He later showed his resolve by refusing to call down an army of angels when his enemies came for him:

Matthew 26:52-54 (ESV) — 52 Then Jesus said to him, “Put your sword back into its place. For all who take the sword will perish by the sword. 53 Do you think that I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than twelve legions of angels? 54 But how then should the Scriptures be fulfilled, that it must be so?”

Jesus clearly had the authority to stop the sequence of events that led to his death, yet he refused to exploit this power, because he considered the needs of others more important than his own. His voluntary descent from glorious transfiguration to shameful humiliation was breathtakingly rapid, and the contrast was surely unforgettable for those first century witnesses.

taking the form of a servant.

The phrase “form of a servant” (morphe doulou) is usually thought to describe the humanity of Jesus, allegedly conveying the idea that he served others during the course of his human existence. The act of “taking” this form is therefore assumed to be the voluntary choice to become a human being.

But we have already seen that “form of God” describes the visibly glorified Messianic Son who represents the invisible God. And we have also seen that the Messiah’s “emptying” describes his voluntary choice to submit to death on a cross. If these things are so, then by implication “form of a servant” describes the visibly afflicted Messiah who represents a class of people identified as servants.

Paul’s teaching in Gal. 4:1-7 illuminates the sort of servanthood he has in view. He points out that before the appointed time to accomplish redemption and receive his inheritance, the Messianic Son was no different from a servant or slave (doulou) in terms of his legal status.27 Jesus was sinless, yet had been born under the law, positioning him to represent other “servants” who were enslaved to sin and therefore in bondage to the penalty of the law:

Galatians 4:1-7 (ESV) — 1 I mean that the heir, as long as he is a child, is no different from a slave [doulou], though he is the owner of everything, 2 but he is under guardians and managers until the date set by his father. 3 In the same way we also, when we were children, were enslaved to the elementary principles of the world. 4 But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, 5 to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons….7 So you are no longer a slave [doulou], but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God.

Given this background, “servant” (doulou) in Phil. 2:8 most likely has in view one who is indebted to the law. The word “form” (morphe) emphasizes the outward appearance, indicating that Jesus took upon himself the visible afflictions of one who is paying the penalty of the law. These afflictions began when he was bound by the guards in Gethsemane (Jn. 18:12). James McGrath thus points out:28

In light of the Gethsemane story, the reference to taking on “the form of a servant” need not be interpreted in incarnational terms, but might envisage more concretely his being led away in captivity from Gethsemane.

It is also instructive that at the time Paul wrote the letter, he and the Philippians were themselves enduring physical afflictions for the sake of the gospel. Just prior to the Carmen Christi, he acknowledges their suffering and points to Christ as their exemplar (Phil. 1:29-2:5). They would therefore expect “form of a servant” to be focused particularly upon the sufferings of Christ. This is later reinforced by Paul’s desire to be “conformed” to the Christ’s death:

Philippians 3:8-10 — 8 More than that, I count all things to be loss in view of the surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whom I have suffered the loss of all things, and count them [mere] rubbish, so that I may gain Christ…10 that I may know Him and the power of His resurrection and the fellowship of His sufferings, being conformed [summomorphoumenos] to His death. 11 if somehow I may attain to the resurrection from the dead.

Paul considers it an honor to embrace this afflicted form of his Savior, recognizing that the glorified “form of God” awaits him on the other side of that affliction. Ultimately, the Carmen Christi points to Christ as the exemplar who was in each of the two forms that his true followers will likewise experience:

- “Form of God” = Glorified Jesus “Conformed to his body of glory” = Glorified followers of Jesus

- “Form of a Servant” = Afflicted Jesus “Conformed to his (body of) death” = Afflicted followers of Jesus29

The difference between Jesus in the “form of God” and the “form of a servant” is truly a dramatic one. On the one hand, the moment of the transfiguration visually depicts him in the glorious “form of God,” confirming him to be the Messianic Son. It represents his ultimate destiny and that of all who follow after him, making it the ideal starting point for the Carmen Christi.

On the other hand, Jesus set aside this glory and took the shameful “form of a servant” in solidarity with those enslaved to the curse of the law. He voluntarily chose to suffer affliction and death on their behalf, setting the example of sacrificial humility as the righteous path to glory. This completes the contrast that Paul began in the opening line of the hymn, making it an excellent place to conclude the first stanza.

In the next post we will consider how the second stanza carries forward the thrust of Paul’s message from a slightly different angle.

- The entire hymn runs from vss. 6-11. We are only considering vss. 6-8 in this two part series. For an examination of vss. 9-11, see Is Jesus Called YHWH in Philippians 2:11? ↵

- The word genomenos is usually translated “born,” but as we will see in Part 2 of this series, it is likely more accurate to render it as “become.” ↵

- Of the 15 major translations surveyed, 13 placed a comma after “servant.” The NLT and NASB95 instead chose to add the conjunction “and” after “servant,” which is also not present in the original Greek. In addition, 13 translations placed a period, colon, or semi-colon after “men.” The YLT and NET used a comma. ↵

- The bar seen above certain words (-) is called a “macron” and it signals that an abbreviation is being used. This is obviously not related to sentence punctuation. ↵

- Moises Silva, Philippians (BECNT), p. 109. ↵

- Silva, p. 110. ↵

- Silva, p. 110. ↵

- See https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/g3444/esv/mgnt/0-1/ ↵

- Peter O’Brien, Philippians (NIGTC), p. 196. ↵

- The single exception is Job 4:16 LXX, where a spirit appeared to Job in an indiscernible “form.” ↵

- The following is a complete list of the occurrences of the noun morphe in the Bible: Phil. 2:6, Phil. 2:7, Mark 16:12, Jdg. 8:18 LXX, Job 4:16 LXX, Isa 44:13 LXX, Dan 4:36 LXX, Dan 5:6 LXX, Dan 5:9-10 LXX, Dan 7:28 LXX, Tobit 1:13 LXX, 4 Macc. 15:4 LXX, Wisd. Sol. 18:1 LXX. ↵

- Rom. 1:20, Col. 1:15, 1 Tim. 1:17. ↵

- Philo, a contemporary of Paul, also treated form (morphe) and image (eikon) as synonyms in the context of man being made in God’s image in Op Mund 1:25. See http://earlyjewishwritings.com/text/philo/book1.html ↵

- Regarding the believer’s inward transformation, Paul uses verbs forms of morphe such as morphothe in Gal. 4:19 and metamorphousthe in Rom. 12:2. ↵

- E.g. Gordon Fee, Philippians (NICNT), p. 531. See also Silva, p. 186 ↵

- Many translations obscure this nuance by rendering the verb huparchon (“being”) in the past tense (usually “was” or “existed”). The Young’s Literal Translation is a notable exception that gets it right. ↵

- Many thanks to my friend Jonathen Favors, who set me on the path of investigating the transfiguration as an interpretive option and assisted in some of my research. ↵

- See Matt. 16:21-17:9; Lk. 9:30-31. ↵

- 2 Corinthians 4:4-6 may offer additional evidence that “form of God” refers to Jesus in his transfigured form. Verse 4 describes Christ as the “image of God,” which was previously shown to be synonymous with the phrase “form of God.” Two verses later, Paul refers to the “light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.” While light is used here as a metaphor for knowledge, Colin Kruse correctly notes: “There is an outward as well as an inward aspect here. Outwardly, on the way to Damascus, Paul saw ‘the glory of God in the face of Christ.'” (Colin Kruse, 2 Corinthians (TNTC), p. 116.) However, the glorified “face” (prosopon) of Christ is never explicitly mentioned in connection with Paul’s Damascus vision. But this word does appear in the account of the transfiguration (Matt. 17:2), suggesting that it may also be in view, since it likewise describes Jesus in his glorified bodily form. ↵

- Craig Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary, p. 316. ↵

- Stefanos Mihalios, The Danielic Eschatological Hour in the Johannine Literature, p. 101. ↵

- The word harpagmos, which literally means to “seize,” has generated quite a bit of scholarly debate over the years. As some scholars have noted, it is possible that this word carries the connotation of “exploit.” For an in-depth technical analysis of the word, see https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.15699/jbl.1351.2016.2978. ↵

- Darrell Bock, Luke 1:1-9:50, p. 872. ↵

- Gordon Fee, p. 306 ↵

- See O’Brien, p. 204 and Fee, p. 306. ↵

- Silva, p. 114. ↵

- The word doulos is variously rendered servant, bondservant, or slave in most English translations. ↵

- James McGrath, “Obedient Unto Death: Philippians 2:8, Gethsemane, and the Historical Jesus,” p. 13. ↵

- While Paul doesn’t use the word “body” in Phil. 3:10, this is clearly implied. See 2 Cor. 4:10. ↵